|

|

|

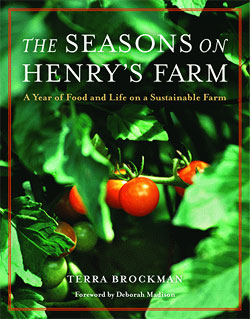

A Suburban Girl Considers the Farm

Jennifer McStotts reviews The Seasons on Henry's Farm: A Year of Food and Life on a Sustainable Farm, by Terra Brockman

As I scanned over the table of contents for The Seasons on Henry’s

Farm: A Year of Food and Life on a Sustainable Farm by Terra Brockman,

I saw that scattered throughout the 52 food-themed weeks that organized the book are a dozen recipes based on farm-fresh foods. On

every page, I saw food, food, food, and I thought: I may not be the

right person to review this book. When I think of food, I think of

foodies and the friends I always hope will invite me to dinner.

Meanwhile, I live in a teeny studio, which means I have a teeny

studio-sized kitchen, with a hot plate that just barely fits between

my sink and my toaster oven, meaning I have room to cook or I have

room to set out my cutting board to do prep, but I do not have room on

the counter for both. When I see a food that’s local or organic or

heaven help me both, I snatch it up. I don’t even think about price,

which is probably why I spend as much on food as I do on rent every

month. I also tend to spend more on prepared foods—tubs of pineapple

chunks and bags of spiced potato slices—because of the challenge of

doing prep work in my kitchen. It’s not that I don’t like to work

with food, to cook, it’s just that in my current place, cooking is a

hassle. As I scanned over the table of contents for The Seasons on Henry’s

Farm: A Year of Food and Life on a Sustainable Farm by Terra Brockman,

I saw that scattered throughout the 52 food-themed weeks that organized the book are a dozen recipes based on farm-fresh foods. On

every page, I saw food, food, food, and I thought: I may not be the

right person to review this book. When I think of food, I think of

foodies and the friends I always hope will invite me to dinner.

Meanwhile, I live in a teeny studio, which means I have a teeny

studio-sized kitchen, with a hot plate that just barely fits between

my sink and my toaster oven, meaning I have room to cook or I have

room to set out my cutting board to do prep, but I do not have room on

the counter for both. When I see a food that’s local or organic or

heaven help me both, I snatch it up. I don’t even think about price,

which is probably why I spend as much on food as I do on rent every

month. I also tend to spend more on prepared foods—tubs of pineapple

chunks and bags of spiced potato slices—because of the challenge of

doing prep work in my kitchen. It’s not that I don’t like to work

with food, to cook, it’s just that in my current place, cooking is a

hassle.

I wondered if I wasn’t going to have to pass this book on to a friend

with more food cred, but then I started to read. Brockman presents a

charming vision of farm life, from scenes you expect of big family

farm lunches and chains of farm helpers tossing melons from the field

to the truck, to scenes a suburban girl like me didn’t expect, little

insights into how farms really work. How one of the helpers etches a

letter into the skin of the melons so everyone can tell their types.

How the author’s brother, Henry, organizes his farm notebooks. How he

cures fresh sweet potatoes in a homemade sauna of space heaters and

wet towels. How much thought is given—must be given—to the

composition of the soil on an organic farm.

Brockman has taken a single year in the life of her family and its

farms and divided it into the 52 weeks of the year, then

grouped them into the traditional lunar agricultural calendar. She

thinks of each of these weeks as “seasons”—the seasons of planting

one crop or harvesting another, seasons based around farm chores like

seed-ordering or slaughtering or fencing, seasons of growing and

dying, seasons based on the feel of the air and the quality of the light. I have to admit that at first I thought the metaphor,

being a bit heavy-handed, might drag after I read about it on the

jacket, in the foreword, and again in the introduction. But in truth,

it fades into the background as a structural element, an unseen

scaffolding around which farm life moves, as soon as you get a few

pages in.

When I say Brockman’s vision is charming, I don’t mean that it is

idyllic or glossy. She neither bemoans nor camouflages the long hours

and hard work of a farming life. What makes this book such a

well-rounded read is how finely Brockman integrates all of these

details together: the beauty of Illinois’ weather and environment, as

well as the consequences it has on farming; the science of soils and

fungi and biology and botany, and the colors they create on a leaf or

flower or fruit; the cycle of life and slaughter, reality and poetry.

The Seasons on Henry’s Farm is a book that can be read one season at a

time or one four- or five-week moon every night; there are many parts

of the book where it was hard to put down. In the spirit of a

family-run farm, Brockman not only varies her own voice, bringing in

family memoir alongside the agriscience narrative for instance, but

she also includes short pieces by her nieces, her brother, and her

father, handing the camera to someone else when she feels they can

better capture the moment, much in the way the family acknowledges

Brockman’s mother to be the only one trusted with tomato sorting and

her brother the finest garlic braider by far.

The only section I skipped was “Week 14: Hog Heaven,” because I have a

complex and emotional personal history with pig slaughter, but the

stories of death, animal and human alike, that Brockman includes in a

faithfulness to her year-on-a-farm structure are some of the most

beautiful in the book. And for each of those is an equally

magnificent moment in nature, a complex scientific explanation made

clear, a historical revelation, and a light-hearted anecdote.

Sometimes, one of Brockman’s scenes serves many of those categories at

once, such as in one of my favorite moments when she contrasts the

beauty of fresh asparagus and our society’s long history of “smelling

asparagus-perfumed chamberpots,” as well as the chemical and genetic

reasons for the odor.

At the end of The Seasons on Henry’s Farm, I remain a suburban girl who

was raised without a root cellar and has no means for engaging in the

kind of deep “waste not, want not” sustainability that the Brockmans strive for everyday, nor do I have the kitchen to do justice to some

of her fantastic-sounding recipes—not yet at least—though many of

them are simple enough that if I can access similar ingredients where I live, I’ll give them a go. Her work made me eager to try the

farmers market near me when it begins again this spring, but more

importantly, it made me feel both grateful for the work of families

like the Brockmans and hopeful that there is a way to reverse the

cycle begun by industrial agriculture in the 20th century.

|

|

|