|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Field Notes Casting Off, About, and Somewhere in Between

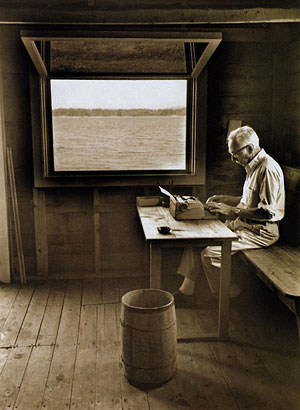

Kathryn Miles aboard the 90-foot yacht she and her partner sailed as part of a small crew to the Mediterranean this summer. Photo courtesy Kathryn Miles. All the sailors I know think often about their first solo sail. It’s a big deal, this moment where one casts off camaraderie and group think to enter, instead, into an exclusive and exceedingly tenuous relationship with wind and water. There’s nothing like such a moment to really hit home the fragile tenacity of one’s own agency. I recently had cause to experience the power of that kind of moment firsthand. That it might have been long in coming only made it all the more palpable. I’ve been on sailboats since I was an adolescent, but I didn’t really get serious about sailing until much later, when a writing project sent me aboard a double-masted windjammer. Sitting on the bowsprit of that boat as we blazed towards an island in the Gulf of Maine, I came to the kind of awareness that usually leads to no good: I was infatuated—smitten in the kind of way that makes people do stupid impetuous things all in the name of crazy blind love. That love has shown no signs of abating in subsequent years. I co-own a 24-foot racing boat with my partner, which we purchased with the proceeds garnered from the transatlantic delivery of a 90-foot yacht. I direct a sailing program here in Maine, where I also teach a women’s evening course on boat handling. But other than those rare instances when I am able to take a school dinghy for a few laps around the pond or I need to move my boat from mooring to dock or back again, it’s never been just me and the boat and the elements. This wasn’t by design. It wasn’t even something about which I was all that conscious. Sailing, like dating or boxing, just seemed like the sort of thing one regularly does with others. It was this very notion of camaraderie that found me working as crew earlier this summer aboard a lovely boat called Gusto. Forty-five feet long and built in the spirit of late 19th century cutters, Gusto evokes a bygone era. Her hull is heavy wood; her interior is filled with cherry joiner work. Instead of a wheel, Gusto boasts a somewhat whimsical tiller. This is clearly a romanticist’s boat. And because I am such a person, I was particularly delighted when her owner, an affable orthopedic surgeon, invited me to help race the boat in the Eggemoggin Reach Regatta. Ours was an easy deal to strike. Gusto’s owner is newly returned to sailing. His daughters were eager to join us but had little boathandling experience. What he needed was someone who could learn the ropes in time for the race and teach a little bit of that learning to others. Perpetual studenthood, I assured him, is my one real vocation. Our first of the three-day competition was a trying one marked by limp winds, becalmed seas, and an overly ambitious course. Bedraggled, we hobbled back to our homes just before midnight. The next morning, Gusto’s owner called me with a request. His daughters, who had arrived the day before on a redeye flight from Los Angeles, were understandably exhausted and hoped to spend the day relaxing with family. Would I be willing, he wondered, to drive the boat to the harbor where the final day’s race would begin?  Boats sailing in the Eggemoggin Reach Regatta. Photo by Kathryn Miles. Of course I was. And so I found myself in the unexpected position of delivering Gusto, alone, the 27 nautical miles or so from Camden to Brooklin, Maine. Twenty-seven miles doesn’t seem like much in the modern mechanized world. But by boat, particularly a sailing boat, it takes the better part of a day. It also, I soon learned, takes a fair piece of courage—at least in the initial embarkation. The harbor where Gusto sat moored is a busy one, made all the more so by the weekend’s regatta. A scrum of racing yachts tacked madly against one another as they prepared for the start of the day’s race; dozens of spectator vessels kept pace alongside. The scene was nothing short of a nautical traffic jam. And as I stood alone in the cockpit of Gusto, the breezy, infatuation-induced confidence with which I had accepted the task turned leaden and quickly sank to the bottom of the harbor. It didn’t matter that I’d spent the better part of a week skippering this boat, or that I have mastered the principals of sail well enough to be entrusted with students and a fleet of dinghies. I was suddenly, icily terrified. That kind of fear makes a mind sharp and in search of the familiar. It sent mine alighting on the work of one of my favorite sailors, the inimitable E.B. White, who wrote evocatively of the “memorial chill” one experiences whenever casting off, alone. White captured that experience in “The Sea and the Wind That Blows,” a lovely but sometimes grim piece that pays homage to the ineffable experience of raising sail. He agonized over these pages, revising them more intensely—and over a far greater period of time—than any of his other essays. When White first drafted it in 1957, the essay’s focus was a kayaker who had just sailed alone across the Atlantic. This accomplishment led White to muse on the thrill of solo sail, but the resulting draft rang hollow for White, and so he soon set it aside. Subsequent drafts proved no more satisfactory; and it was not until six years later that he would complete the panegyric to all that is wonderful and terrifying about a life afloat. For White, this brilliant paradox derives from the simultaneous experience of the known and the unknown that occurs under sail: the “strange promise” and “hint of trouble” that compels one to confront what is just beyond our reach—and our control. There is yearning and exhilaration in such an experience—the kind that compels one out again and again. It was this very yearning that eventually compelled me to drop Gusto’s mooring line, scuttle through the school of tacking yachts, and then navigate past the shoally islands guarding the bay. From there, I entered the Eggemoggin Reach itself and found that fear and dread had been replaced with spirited euphoria: I wanted nothing more than to be right where I was. The Eggemoggin Reach (shown as A in the interactive map to the right) and its eponymous regatta are famous for all sorts of reasons. Each year, the regatta draws over 100 wooden vessels, including schooners, early 20th century racing yachts, and contemporary experimental craft. The Reach itself, a narrow 10-mile long dogleg separating the mainland from Deer Isle and connecting the Penobscot and Jericho Bays, is one of the best sailing grounds in the world, thanks to its pristine waters, iconic coastline, and dependably beamy winds that lead one to the coves of Brooklin. It’s here that Joel White, E.B.’s son and one of the world’s best designers of wooden boats, chose to locate his boat yard. Inspired by the geography of the place, Joel created a design aesthetic based on a deceptively simple philosophy: beautiful boats are better than plain ones, and the simplest boats are almost always the most fun. White’s son, Steve, now runs the Brooklin Boat Yard. He is also the founder of the Eggemoggin Reach Regatta, which he continues to oversee with the kind of enthusiasm that says he, too, is besotted by boats. And, if asked, he readily admits that this love, like that of his father’s, derives from the days spent sailing the Reach with E.B. Although E.B. White hailed from New York, he considered Brooklin, Maine, his real home. He did most of his writing in a spartan boathouse with a single square window that opened onto the craggy coastline of the Reach. When writing proved too troublesome, he abandoned it for an afternoon sail, which he readily confessed was his greatest pleasure. Afloat, he wrote, life is “compressed in orderly miniature and liquid delirium.” When that compression occurs along coniferous coves unchanged since first contact, the experience tends towards a transcendent one. Maybe that’s why White was also fiercely guarded about the sanctity of Brooklin and its Reach. Those on a literary pilgrimage to meet the creator of Charlotte and her famous pig often stopped by the General Store—the only retail business in town—for directions to E.B. White’s house. Without fail, such requests were met with blank stares and the assurance that no one in town had ever heard of a man by the name of White. When E.B. submitted to a rare interview, he beseeched the reporter not to give away his exact location. Perhaps, he suggested, “you can say ‘somewhere on the Atlantic Coast.’ If you must, make the location the way the property appears on nautical maps—Allen Cove. That way no one will be able to find it except by sailboat and using a chart.”  E.B. White writes in the boathouse in Brooklin, Maine. Photo by Jill Krementz, courtesy Shedworking. White liked what was required in this: reading not bound pages, but rather, landscape and the ephemerality of wind and wave. As far as he was concerned, they were the only real way to prove not just what you know, but that you know. That kind of epistemology resonates deeply with me, particularly when I’m somewhere as richly knowable as the Eggemoggin Reach. And so, standing as I was behind the tiller of a wooden boat that recent day, I found myself in the delightfully entitled position not just of looking for E.B. White in each passing inlet and puff of wind, but also knowing I was following his preferred directive as I did. Memorial chill aside, E.B. White liked to sail alone. He preferred to navigate not with charts, but rather, with all the “wariness and ignorance of the early explorers.” Probably he would have frowned upon the GPS and satellite systems installed on Gusto. Certainly he would have been amused that the stubbiness and placement of her tiller meant I could reach neither. Sailing alone and unencumbered requires, after all, a kind of immediacy, which is to say an ability not so much to read as to interpret. It’s about using one’s own agency as a way of establishing meaning. To negotiate, not in the sense of haggling, but rather in the sense of striving towards successful travel. This is an active process, one that requires us to fill in the gaps by our own accord. That gap filling, I think, is precisely what can be so frightening when it comes to any act of interpretation. It’s not something we have cause to do much, nor is it something we’re necessarily all that good at. But we ought to be. I’m certainly not the first to advocate for as much. Matthew Crawford, author of Shop Class as Soul Craft, advocates a rejection of universal knowledge in favor of individual experience. The problem with the former, he argues, is that it endeavors to exist independent of place. “In fact,” he writes, by its very nature “such knowledge aspires to a view from nowhere.” Individual experience, on the other hand, is all about the formation of what Crawford calls practical know-how: the kind of knowledge that depends upon our own lived experiences. These lived experiences are incomplete. To exist in a meaningful way, they must remain married to context and embodied in those who live them. E.B. White never said as much, but I have to think that that was what most resonated in his love affair with sailing. Certainly, it gets at the very heart of why a solo voyage is so meaningful for sailors. And, in truth, it’s why I will journey back out there again and again and again, forever embracing that chill and what it has to offer.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home : Archives : News Terrain.org : https://www.terrain.org Terrain.org is a publication of Terrain Publishing. |

||