|

|

|

A Stone’s Throw Bedrock: Coming to a Language of Earth  Early morning mist at Cape Royal, North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Earth is our origin and home. The elements making this world, our bodies, and all life come from the dust of ancient stars—we are thus bound together in time, space, and substance. When I say such things early in a semester, students dutifully copy the words into their notebooks, ready to memorize them on demand. But they will not be asked to regurgitate “facts” or just demonstrate some proficiency in the language of science. The basic question to them—How do we know Earth?—can be answered in countless ways, and I urge these students to begin with themselves, with what they perceive in the world and how they sense it. While contemplating human life and the life of the planet itself, they also pay attention to what is awakened within, to evoked emotions or felt hunger. For, as we soon consider, how we remember and record our living in this physical world becomes a basis of relationships that are built upon and fitted within a larger pattern of existence. I am secretly selfish, too, in providing such space for our individual senses of wonder in courses on Earth and environmental history. “Geology” comes from the Greek geo- (Earth) and -logia (discourse, study of), and I’ve always taken its root meaning broadly. Perhaps this proclivity originated with the astonishment and wonder I felt at the age of four or five, pondering not just what made Earth and sky but what they meant to each other and what I meant to them. That they and we were great friends I was certain. The landscapes or environments in which our species evolved—and the component elements of rock, soil, and water—imprinted us from our first tentative breaths. In The Language of Landscape, Anne Spirn writes that “Humans touched, saw, heard, smelled, tasted, lived in, and shaped landscapes before the species had words to describe what it did. Landscapes were the first human texts, read before the invention of other signs and symbols.” The ties have always been reciprocal. From ancient times to the present Earth’s faces have left their marks in cultural traditions and individual imagination—many languages and worldviews originated out of salient elements of people’s social and physical settings, reflecting the rhythms of the land. But humankind has also marked and changed Earth’s surface to a great extent—by changing the atmosphere’s composition, by threatening biological diversity and ecosystem integrity, by enlarging our already heavy ecological footprint. We’ve now created, echoing Bill McKibben, a world substantially different from the one that each of us was born into.  Petroglyph in a sandstone wall, Dinosaur National Monument. Photo by Lauret Savoy. How do we know Earth? While natural scientists might study complex chemical, physical, and biological systems interacting through the planet’s long existence, the history of human exploration, settlement, habitation, and land use also tells of complex encounters between different cultures and Earth. Oral tradition, art, literature, scientific theories—stories of imagination and knowledge—all attempt in their own ways to question and understand this world and humankind’s place in it. Earth’s many landscapes (its rivers, mountains, canyons, plains, deserts), Earth’s materials (rock, soil, water), and its events or processes (volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, floods, and erosion) hold prominent places in all forms of expressive media. So does time, the deep time of origins. These elements offer powerful metaphors on human identity and memory, inviting us to understand ourselves in the contexts of habitat and home. What follow are a few examples of written expressions in poetry, fiction, and nonfiction of such wonder and imagination. Rock and Stone Rock and stone speak of history and origins. The paths of human cultures and our built environments have taken direction and shape from the material basis rock provides in the lay of the land and in the yielding presence of extractable “resources.” Yet each pebble, each grain of sand, each rocky outcrop is also a relic of former worlds—of mountains uplifted and eroded long ago, of erupted volcanoes, of the planet’s shallow interior intruded and metamorphosed. One scientific prize is the ability to decipher a tangible memory of Earth history, process, and structure from what remains after weathering and erosion.  Stonework of Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. Photo by Lauret Savoy. But vocabularies of different cultural experiences, including literary and artistic expression, also have taken shape and meaning from rock, mineral, and stone. They have reflected on the elemental connections of place in identity, particularly in traditional societies; on patterns, textures, and design; on rock as a framework of our experience on Earth and a metaphor of memory. I recall Zora Neale Hurston’s words from Dust Tracks on a Road: “Like the dead-seeming cold rocks, I have memories within that came out of the material that went to make me.” British archaeologist and writer Jacquetta Hawkes describes in A Land, her award-winning meditation on Great Britain, how life “has grown from the rock and still rests upon it.”

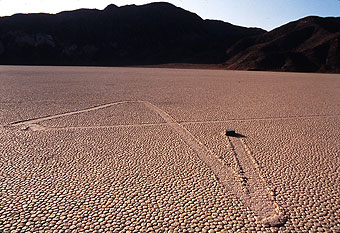

It should be no surprise that the many architectural forms that emerged around the world over time owe much to the distinctive qualities of each region’s native stone. Writing of the lakes and islands of southern Ontario and adjacent Minnesota, Louise Erdrich notes that in the language of her people, the Anishinaabe (or Ojibwe), the “word for stone, asin, is animate.”  Racetrack Playa, Death Valley National Park, California. Photo by Lauret Savoy. “After all,” she adds, “the preexistence of the world according to [Anishinaabe] religion consisted of a conversation between stones. People speak to and thank stones in the sweat lodge, where the asiniig are superheated and used for healing. They are addressed as grandmothers and grandfathers. Once I began to think of stones as animate, I started to wonder whether I was picking up a stone or it was putting itself in my hand. Stones are no longer the same as they were to me in English.” Hikaru Okuizumi’s novel The Stones Cry Out, winner of Japan’s Akutagawa Prize, relates how an encounter with a dying corporal—a geologist—on a Philippine island in the Second World War led a Japanese soldier who survived to become “a fanatic of stones.” Late at night, in his attic, he’d gaze through a microscope at thin slices of rock, thinking that “even the smallest stone in a riverbed has the entire history of the universe inscribed upon it.”

Antelope Canyon, Arizona. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Or consider the last stanza of Charles Simic’s poem “Stone:”

Deep Time We barely have an inkling of eternity’s mystery. Human perceptions of time and Earth’s antiquity have varied through the ages and across cultures. Conceived of as infinite and finite, linear and circular, continuous and fragmented, time has stood in human thought as metaphor, myth, and scientific “absolute.” But grasping the immensity of all history, of what writer John McPhee has called “deep time,” all but eludes us. Students in geology and biology courses are often asked first to imagine all of Earth’s 4.5-billion-year existence fitting within a single calendar year that ends at the present moment, and then to estimate when in that condensed Earth-year humans evolved. Rarely do they guess that current science places our species’ first appearance on the scene very late on December 31st. James Joyce tried to imagine the “awful meaning” of immeasurable eternity in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man:  Double Arch, Arches National Park, Utah. Photo by Lauret Savoy.

Erosion and tectonic forces have continually redesigned Earth’s landscapes through time, making change the one constant. Pebbles, sediment as strata, or the external shape and internal structure of landscapes are at best partial and incomplete evidence of ancient worlds and changing environments. A forensic effort is needed to piece together a coherent story of this complexly dynamic past. It might be a bit disconcerting to realize, when trying to remember our own origins, that much of Earth’s memory is unknown and unknowable. In Fugitive Pieces, Anne Michaels explores the intersections of Earth history and human memory in stone:

Near Zabriskie Point, Death Valley National Park, California. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Responses to unfamiliar landscapes often resort to comparisons with what is known and familiar. Such was the case in 19th century America for many overland pioneers and members of western exploratory surveys encountering the erosional topography of the vast, semi-arid western plains and drylands west of the 100th meridian. More often than not writings in journals and survey reports refer to “oppressive” senses of both ruinous decay and lost worlds. Joseph Leidy’s 1873 Contributions to the Extinct Vertebrate Fauna of the Western Territories is one of the most eloquent examples. Here the noted American paleontologist and anatomist reflects on the fossil-bearing badland landscape of Wyoming Territory:

Vernal Falls, Yosemite National Park, California. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Water Work It should be no mystery why waters call us. Earth truly is a blue planet, with two-thirds its surface submerged. Life as we know it originated in the world’s oceans, billions of years ago—and when the ancestors of our ancestors finally emerged from that liquid world to take tentative steps onto land they brought the sea within them. Our bodies and those of all other animals and plants—all fragile organic containers—consist largely of water. The human brain is three-quarters, our blood four-fifths, and our lungs nearly nine-tenths water by weight. Even biochemical processes that sustain life, such as photosynthesis, require water as a key ingredient. Clouds extend the reach of the sea over land—far beyond our bodily containers—in the rain and snow that gather in rivulets to form streams and rivers. These waters, repeatedly cycling from clouds to rivers to the sea and back by evaporation, have sculpted more of Earth’s landscapes than any other agent of erosion or deposition. All waters are one, and they remember. Writing of his Kentucky landscape in “A Native Hill,” Wendell Berry provides intimate detail of the erosive work of a stream and hillside he knows well:

Marble Canyon, Kootenay National Park, British Columbia. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Children and small animals also encounter water and its stories, as with Kenneth Grahame’s classic The Wind in the Willows, when Mole suddenly “stood by the edge of a full-fed river:”

Mountains Mountains have always played primary roles in narratives of our dynamic Earth. Many geologic theories over the last few centuries attempted to explain their existence as some form of uplift: that mountains are the product of Earth’s “skin” wrinkling as it contracted, not unlike a drying apple or plum; that they are the products of long-linear troughs of sediments that somehow reversed their downward movement to be pushed skyward; and, most recently, that mountains primarily form along tectonic plate margins where intense forces bend, break, displace, and uplift rocks. Volcanoes, the mountains born of fire, give dramatic surface expression to Earth’s internal heat engine. John Ruskin, the great British art critic and social commentator of the Victorian Age, reflected in Modern Painters on the nature of mountains as part of Earth’s “body.” In his view, “Mountains are, to the rest of the body of the earth, what violent muscular action is to the body of man. The muscles and tendons of its anatomy are, in the mountain, brought out with fierce and convulsive energy, full of expression, passion, and strength.”  Glaciated Titcomb Basin, Wind River Mountains, Wyoming. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Mountains and highlands also exhibit a sacred order that has contributed to ritual and oral tradition of indigenous peoples around the world. As such, mountains are elements in narratives on boundaries and the origin of things, places, and humans for many cultures. In “Look to the Mountaintop” Tewa poet and scholar Alfonso Ortiz (of San Juan Pueblo) considers the complex mosaic of overlapping tribal worlds defined by mountains in the American Southwest:

Mud cracks after a summer storm. Photo by Lauret Savoy. Coming to Bedrock We as humans—as biological organisms, as social beings, and as unique individuals—acquire meaning through sensing and questioning Earth in innumerable ways. Yet how many of us honestly reflect on the stories we tell of this physical world, and of ourselves in the world, and then attempt to live by such stories? Our knowledge of Earth is informed by broad human experiences that have grown from encounters of perception and imagination as well as encounters of process and use. Far from any simple argument of environmental determinism, our lives have always taken place within cultural, geological, and ecological contexts. In Language of the Earth, F. H. T. Rhodes writes that knowledge “becomes meaningful, useful and intelligible as we grasp, not only its content, but also its basis, its implications, its relationship and its limitations. Its coherence and significance lies in its relatedness to the whole of the rest of our human experience.” Realizing the circumstances, conditions, and contexts in which we live (and die) on Earth, in which each of us is intimately part, amounts to coming to bedrock—that is, returning to a secure foundation, to basic principles, to an elemental essence, in addition to acknowledging the solid ground beneath our feet.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||